Many consider these similarities homages, a practice as long as the history of cinema itself, a way for Tarantino to pay respect to the movies he loves.

But Tarantino denies this. In the same interview, he goes on to say, “Great artists steal. They don’t do homages.”

It’s a quote that closely resembles words attributed to another famous artist: Pablo Picasso, who’s often quoted as having said, “Good artists copy, and great artists steal.” To understand why and how Tarantino steals, it’s important to understand his background.

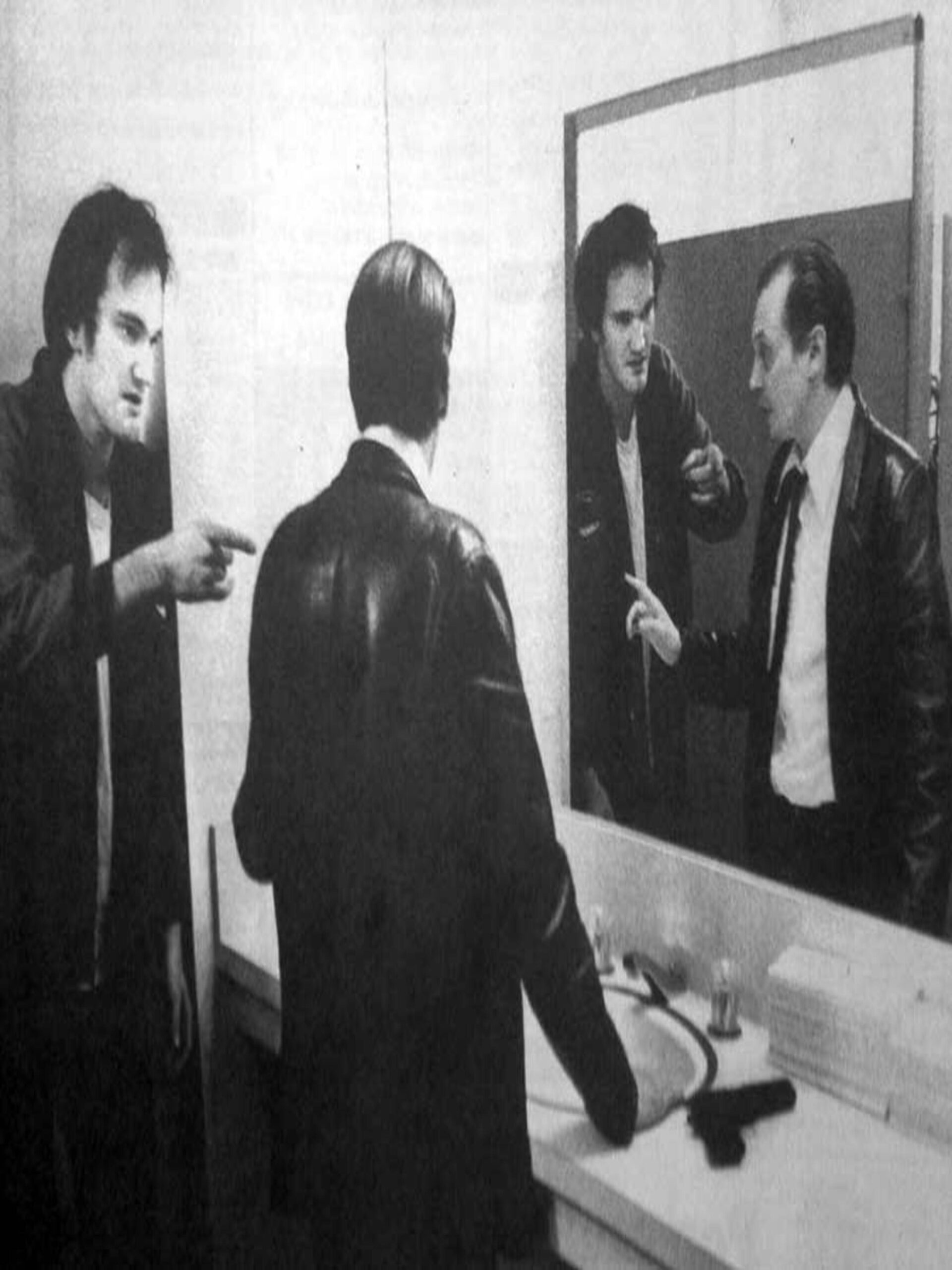

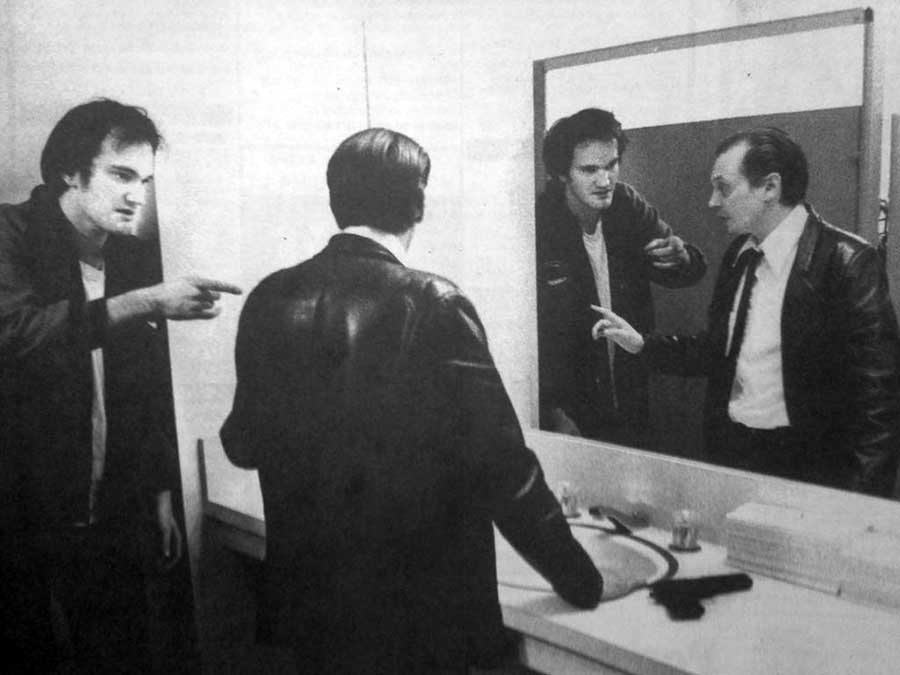

Tarantino’s career in film didn’t start in a classroom or even a movie set, but a video store, where he worked as a clerk and gained a reputation for his almost encyclopedic knowledge of cinema. In other words, Tarantino was never taught how to make a film.

Instead, he learned how to make films by watching them, which makes it natural that imitation became his main source of inspiration and style.And as paradoxical as it may sound, Tarantino’s movies have a sense of originality to them, despite their many sources of inspiration.

This is why Tarantino is often hailed as one of the essential filmmakers of postmodernism. Postmodernism in film describes an era when filmmakers began questioning the ways in which mainstream movies are made and told and began making movies that went directly against it.

One of the central tenets of postmodernism is the idea that nothing is new in art; everything is recycled and reused over and over again.

“Reservoir Dogs” might have stolen the Mexican standoff from “City on Fire,” but “City on Fire” also stole it from the 1966 film “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.What makes Tarantino so special is that he never steals from one source.

He rather steals from multiple sources spanning decades and then stitches them together to create something new. It’s a technique known as pastiche, a vital element in postmodernism.

And if you take a look at Tarantino’s career, each of his eight films is a tribute to a specific genre and movement in cinema. “Reservoir Dogs” is a pastiche of the gritty Hong Kong crime films, and “Pulp Fiction” is based on the unconventional French New Wave movement.

“Jackie Brown” basis itself off the ’70s’ controversial blaxploitation films, while “Kill Bill” is reminiscent of the classical Japanese samurai and Chinese kung fu movies.

“Death Proof” pays tribute to low-budget exploitation movies, while “Inglourious Basterds” references World War II cinema. And his two most recent films, “Django Unchained” and “The Hateful Eight,” are modern takes of the Italian spaghetti Westerns.

Tarantino seamlessly blends all these genres and inspirations through his unique vision and writing.